The AP English Language and Composition course is designed to enable students to become skilled readers and writers in diverse genres and modes of composition. As stated in the Advanced Placement Course Description, the purpose of the Language and Composition course is “to enable students to read complex texts with understanding and to write papers of sufficient richness and complexity to communicate effectively with mature readers” (The College Board, May 2007, May 2008, p.6).

Wednesday, September 30, 2015

Tuesday, September 29, 2015

The Vietnam in Me

The Vietnam in Me

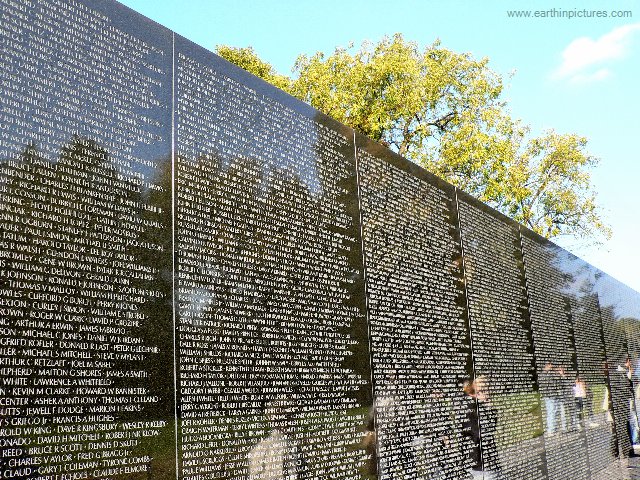

My Lai

THE VIETNAM IN ME: MULTIPLE TRUTHS IN THE LIFE OF TIM O’BRIEN

“THE VIETNAM IN ME.” NEW YORK TIMES MAGAZINE, OCTOBER 2, 1994.

Comment:Tim O’Brien has explained multiple times throughout the novel that everything he writes is absolute fiction, even though it may be inspired by actual events, but maintains a special term which is classified story truth (in the sense that it’s true that it is a story and may have happened). He also uses the term happening-truth, which is what is actually occurring in reality. These two clash with the release of the short story “Field Trip” and the article “The Vietnam In Me”, both about his return to Vietnam.

The first, “Field Trip”, is a prime example of story truth, where O’Brien speaks about how he and his daughter return to Vietnam and he goes to the field where Norman Bowker let go of Kiowa and O’Brien wades in and buries Kiowa’s moccasins at the spot where he went under. He then has a heart-to-heart conversation with his daughter on the nature of the Vietnam War and gives a great deal of polished-over romanticism on loss and grief and duty (almost as if you combined Nathaniel Hawthorne, Keanu Reeves, and Tom Clancy for a made-for-TV movie).

Meanwhile, “The Vietnam In Me” is the realistic, factual account of O’Brien’s return to Vietnam, with a female friend (not his daughter), and his return to his own personal killing fields (apologies for the incorrect placement of that term, seeing as killing fields were in Cambodia and not Vietnam). In this account, it’s as though O’Brien allowed Larry Clark to follow him around with a camera and detail everything on his journey through ‘Nam. From visiting the minefields that took the lives of his friends with former VC and NVA officers, to the village of My Lai where American militarism truly failed in 1968, and even to stuffy, hot Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) hotels where he battles his own personal demons on the “terrible things” he did during the war, though not giving any evidence as to what those things were. The article even takes a turn for the even darker with his constant contemplation of suicide after his female friend leaves him. While this article is much more gritty than the short story, one thing remains the same: his feelings. Throughout both pieces, he cannot escape this insufferable sadness and guilt over the unknown.

“The Vietnam In Me” is more true because O’Brien says that truth is in the gut and this is where O’Brien’s gut is. Based off his writing style alone, one can just literally feel the emotions sweep off the page and hit him or her right in the chest while with “Field Trip”, it’s as if one can almost see the time it took in calculating the perfect emotions and perfect snippets of dialogue for each character from the uncertaintity as to what to say at Kiowa’s death spot to him telling his daughter that the Vietnamese was not angry at him because “all that’s over now”. Almost cliche even though it works wonderfully with the rest of the book. One shouldn’t get upset about the fact that one story is based on fact and the other is based in fiction; it is one’s personal choice to like or dislike whatever they read. And the question of getting upset brings up another question of whether it would be better to stick to the truth or to emotional fiction, and once again, it is whatever one wants. Personally, I would like truth with emotions clearly portrayed so not only do I know what actually happened, but I also know what the people were feeling at the time.

Monday, September 28, 2015

In the Field and Good Form (cont.)

AGENDA:

Discuss "In the Field" and "Good Form"

TEST: Friday, 20 Figurative Language Terms

and first column of spelling

http://grammar.about.com/od/rhetoricstyle/a/20figures.htm

HMWK: Read O'Briens "The Vietnam in Me" for tomorrow

Read the remaining chapters for discussion on Wednesday.

Chapter 19: “Field Trip”

1. Why does O’Brien return to the shit field? 2. What is the point of putting Kiowa’s moccasins in the ground (burying them)? 3. Explain the significance of the final sentence. Who or what is “all finished”?

Chapter 20: “The Ghost Soldiers”

1. What does “The Ghost Soldiers” add to the book that we have almost COMPLETED ? Does it provide any new insights, perspectives, or experiences about any of the characters? What do you think its function in the overall narrative might be?

? Does it provide any new insights, perspectives, or experiences about any of the characters? What do you think its function in the overall narrative might be?

2. Does your opinion of O'Brien change throughout the COURSE of the novel? How so? How do you feel about his actions in “The Ghost Soldiers”?

of the novel? How so? How do you feel about his actions in “The Ghost Soldiers”?

3. “The Ghost Soldiers” is one of the only stories of The Things They Carried in which we don't know the ending in advance. Why might O'Brien want this STORY to be particularly suspenseful?

to be particularly suspenseful?

4. Explain the significance of the title of this chapter.

Chapter 22: “The Lives of the Dead”

1. How does the opening paragraph frame the STORY we are about to read?

we are about to read?

2. Why is O'Brien unable to joke around with the other soldiers? Why does the old man remind him of Linda?

3. What is the function of the Linda plot in “The Lives of the Dead”? Consider in particular what it teaches him about death, memory, storytelling.

4. What is the “moral” of the dead KIAs? Consider Mitchell Sanders' view.

5. In many ways, this book is as much about STORIES , or the necessity of stories, as it is about the Vietnam War. According to O’Brien, what do stories accomplish? Why does he continue to tell stories about the Vietnam War, about Linda?

, or the necessity of stories, as it is about the Vietnam War. According to O’Brien, what do stories accomplish? Why does he continue to tell stories about the Vietnam War, about Linda?

6. Reread the final two pages of this book. Consider what the young Tim O’Brien learns about storytelling from his experience with Linda. How does this knowledge prepare him not only for the war, but also to become a writer? Within the parameters of this story, how would you characterize Tim O’Brien’s understanding of the purpose of fiction? How does fiction relate to life, that is, life in the journalistic or historic sense?

Overall:

1. Assume for a moment, that the writer, Tim O’Brien, created a fictional main character, also called Tim O’Brien, to inhabit this novel. Why would the real Tim O’Brien do that? What would that accomplish in this novel? How would that strengthen a book about “truth”?

2. Finally, if O’Brien is trying to relate some essential details about emotional life – again as opposed to historic life – is he successful in doing that? Is he justified in tinkering with the facts to get at, what he would term, some larger, story-truth?

3. On the copyright page of the novel appears the following: “This is a work of fiction. Except for a few details regarding the author's own life, all the incidents, names, and characters are imaginary.” How does this statement affect your reading of the novel?

Discuss "In the Field" and "Good Form"

TEST: Friday, 20 Figurative Language Terms

and first column of spelling

http://grammar.about.com/od/rhetoricstyle/a/20figures.htm

HMWK: Read O'Briens "The Vietnam in Me" for tomorrow

Read the remaining chapters for discussion on Wednesday.

Chapter 19: “Field Trip”

1. Why does O’Brien return to the shit field? 2. What is the point of putting Kiowa’s moccasins in the ground (burying them)? 3. Explain the significance of the final sentence. Who or what is “all finished”?

Chapter 20: “The Ghost Soldiers”

1. What does “The Ghost Soldiers” add to the book that we have almost COMPLETED

? Does it provide any new insights, perspectives, or experiences about any of the characters? What do you think its function in the overall narrative might be?

? Does it provide any new insights, perspectives, or experiences about any of the characters? What do you think its function in the overall narrative might be?2. Does your opinion of O'Brien change throughout the COURSE

of the novel? How so? How do you feel about his actions in “The Ghost Soldiers”?

of the novel? How so? How do you feel about his actions in “The Ghost Soldiers”?3. “The Ghost Soldiers” is one of the only stories of The Things They Carried in which we don't know the ending in advance. Why might O'Brien want this STORY

to be particularly suspenseful?

to be particularly suspenseful?4. Explain the significance of the title of this chapter.

Chapter 22: “The Lives of the Dead”

1. How does the opening paragraph frame the STORY

we are about to read?

we are about to read?2. Why is O'Brien unable to joke around with the other soldiers? Why does the old man remind him of Linda?

3. What is the function of the Linda plot in “The Lives of the Dead”? Consider in particular what it teaches him about death, memory, storytelling.

4. What is the “moral” of the dead KIAs? Consider Mitchell Sanders' view.

5. In many ways, this book is as much about STORIES

, or the necessity of stories, as it is about the Vietnam War. According to O’Brien, what do stories accomplish? Why does he continue to tell stories about the Vietnam War, about Linda?

, or the necessity of stories, as it is about the Vietnam War. According to O’Brien, what do stories accomplish? Why does he continue to tell stories about the Vietnam War, about Linda?6. Reread the final two pages of this book. Consider what the young Tim O’Brien learns about storytelling from his experience with Linda. How does this knowledge prepare him not only for the war, but also to become a writer? Within the parameters of this story, how would you characterize Tim O’Brien’s understanding of the purpose of fiction? How does fiction relate to life, that is, life in the journalistic or historic sense?

Overall:

1. Assume for a moment, that the writer, Tim O’Brien, created a fictional main character, also called Tim O’Brien, to inhabit this novel. Why would the real Tim O’Brien do that? What would that accomplish in this novel? How would that strengthen a book about “truth”?

2. Finally, if O’Brien is trying to relate some essential details about emotional life – again as opposed to historic life – is he successful in doing that? Is he justified in tinkering with the facts to get at, what he would term, some larger, story-truth?

3. On the copyright page of the novel appears the following: “This is a work of fiction. Except for a few details regarding the author's own life, all the incidents, names, and characters are imaginary.” How does this statement affect your reading of the novel?

Friday, September 25, 2015

"In the Field" and "Good Form"

AGENDA:

Review "Speaking of Courage" and "Notes"

Go over AP Paper #1, Quiz #2 (hand in on Monday for full credit), and vocabulary for next week (Top 20 Figures of Speech)

HMWK: Complete Packet #1

Read "In the Field" and "Good Form"

Begin studying Top 20 Figures of Speech

Review "Speaking of Courage" and "Notes"

Go over AP Paper #1, Quiz #2 (hand in on Monday for full credit), and vocabulary for next week (Top 20 Figures of Speech)

HMWK: Complete Packet #1

Read "In the Field" and "Good Form"

Begin studying Top 20 Figures of Speech

Discussion Questions for Monday (look over):

“In the Field”

1. Briefly summarize the plot and style of the story. Is this story more of a “true” war story than the account in the chapter “Speaking of Courage”?

2. What point of view is used to narrate “In the Field”?

3. Why is the young man not identified in the story? What is the character’s purpose in the narrative?

4. In “In The Field,” O'Brien writes, “When a man died, there had to be blame.” What does this mandate do to the men of O'Brien's company? Are they justified in thinking themselves at fault? How do they cope with their own feelings of culpability? Consider all of the characters.

5. What, in the end, is the significance of the shit field story (or stories)?

“Good Form”

1. In “Good Form,” O'Brien casts doubt on the veracity of the entire novel. Why does he do so? Does it make you more or less interested in the novel? Does it increase or decrease your understanding? What is the difference between “happening-truth” and “story-truth?”

1. Briefly summarize the plot and style of the story. Is this story more of a “true” war story than the account in the chapter “Speaking of Courage”?

2. What point of view is used to narrate “In the Field”?

3. Why is the young man not identified in the story? What is the character’s purpose in the narrative?

4. In “In The Field,” O'Brien writes, “When a man died, there had to be blame.” What does this mandate do to the men of O'Brien's company? Are they justified in thinking themselves at fault? How do they cope with their own feelings of culpability? Consider all of the characters.

5. What, in the end, is the significance of the shit field story (or stories)?

“Good Form”

1. In “Good Form,” O'Brien casts doubt on the veracity of the entire novel. Why does he do so? Does it make you more or less interested in the novel? Does it increase or decrease your understanding? What is the difference between “happening-truth” and “story-truth?”

AP Paper #1

AP

ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND COMPOSITION

Marking

Period #1 Major Paper

DUE: Monday October 12, 2015

ANALYSIS

ESSAY: Tim O’Brien’s The Things

They Carried

Requirements:

- A clear thesis statement and introduction which sets out for your reader the point you wish to make about the stories.

- A very brief synopsis of the stories you are discussing. This means writing a sentence or two about each story (no more than one paragraph in total).

- An analysis supported by examples from the text, properly quoted (or paraphrased) and cited.

- You are not required to use sources other than O’Brien’s book to support your views; if you do use any outside sources, make sure you properly quote or paraphrase and cite. Note, however, that the use of outside sources for this essay is strongly discouraged!

- Length: 4-5 pages

- All drafts must be typed (10 or 12 font), double-spaced, 1" margins. .

- Must have a title other than the book title.

- Use MLA format for citing. You are not required to use a separate sheet of paper for Works Cited.

Possible topics:

1. Storytelling: Fact or Fiction

Like most of the literature of the Vietnam war, ''The Things

They Carried'' is shaped by the personal combat experience of the author.

O'Brien is adamant, however, that the fiction not be mistaken for factual

accounts of events. In an interview with Michael Coffey of Publishers Weekly soon after the book

was published, O'Brien claims: ‘‘My own experience has virtually nothing to do

with the content of the book.’’ Indeed the title

page of

the book announces it as ''a work of fiction.'' The book is dedicated, however,

''to the men of Alpha Company, and in particular to Jimmy Cross, Norman Bowker,

Rat Kiley, Mitchell Sanders, Henry Dobbins, and Kiowa." O'Brien himself

was an infantryman in Alpha Company and was stationed in the Quang Ngai

province in 1969-70. When asked about this device in an interview with Martin

Narparsteck in Contemporary Literature,

O'Brien explains: "What I'm saying is that even with that

nonfiction-sounding element in the story, everything in the story is fiction,

beginning to end. To classify different elements of the story as fact or

fiction seems to me artificial. Literature should be looked at not for its

literal truth but for its emotional qualities. What matters in literature, I

think, are the pretty simple things--whether it moves me or not. Whether it

feels true. The actual literal truth should be superfluous."

2. THEME AND CHARACTERIZATION:

What is the role of shame or guilt in the

soldier’s lives? How does it

affect their actions? Does it make

them heroic or cowardly? Which stories reflect this theme?

3. CHARACTERIZATION:

What role do women play in the novel—as friends,

lovers, daughters, mothers, dancers, warriors, etc.? This topic covers the entire book, but try to keep your

focus

specific to particular stories and examples.

4. THEME:

What is the role of death in the book? Is it a something to be feared or a

perhaps an escape from the nightmare of war?

5. STRUCTURE:

You may want to focus your analysis on the

structure of the novel and how the stories and reflections interconnect to

present a larger picture.

6. STYLE:

You may want to focus your analysis on

elements of REALISM and MAGIC

REALISM in the novel, or perhaps

you might want to discuss METAFICTION—how this is a novel about fiction.

7. DICTION:

Tim

O'Brien's writing constantly seeks to give meaning to the events that happened

in Vietnam. Create a written portrait of Tim O'Brien using three or four

carefully selected passages that describe the narrator's inner thoughts as

evidence to support your ideas. What does each reveal about his concerns,

hopes, and fears? How do certain word choices reveal the way he sees the world?

8. Your choice: Discuss with Ms. Gamzon

Most Common AP Class Errors

1. Beginning sentences with “and” or

“but”

2. Fragments and run-ons

-Refer back to Strunk and White

3. Not adhering to MLA format

-12 pt., Times New Roman Font

-Double Spacing

–Block Quotes: When including quotes

four lines or more in length, single space and indent the selection

-Citing an author (Author’s last name (no comma) page #)

-Placing the period within the quotation marks or at the end

of a citation

4. Not using the present tense when

talking about a literary piece of work

5. Not properly using quotes

-Using quotes as filler rather than as

support for your ideas

Using partial quotes can be a good fix for this

-Listing quotes rather than introducing

them

Quotes should not float within your writing; they should tie in

with your argument

-Never using

quotes and just summarizing the work

6. Not placing the thesis at the end

of the first paragraph

-This is where the reader is expecting to find your thesis

-This guides your reader for what is to come

7. Improper introductions and

conclusions

-Using phrases such as “in conclusion,”

“finally,” or “ultimately”

-Not writing a hook for the

introduction

Refer to:

Use

a hook:

homeworktips.about.com/od/essaywriting/a/hook.htm

Thursday, September 24, 2015

Norman Bowker/Kiowa

AGENDA:

Review quiz

Pass out 1st packet

Review quiz

Pass out 1st packet

Group One (Speaking of

Courage):

(1) To begin with, why

is this story called "Speaking of Courage"?

Assume the title does NOT hold any irony. In what sense does this story speak of courage?

Assume the title does NOT hold any irony. In what sense does this story speak of courage?

(2) Why does Norman Bowker still feel

inadequate with seven metals? And why is Norman's father such a presence in his

mental life? Would it really change Norman's life if he had eight metals, the

silver star, etc.?

(3) What is the more difficult

problem for Norman--the lack of the silver star or the death of Kiowa? Which

does he consider more and why?

(4) Why is Norman unable to relate to

anyone at home? More importantly, why doesn't he even try?

Group Two (Notes):

(5) In

"Notes," Tim O'Brien receives a letter from Norman Bowker, the main

character in "Speaking of Courage." Why does O'Brien choose to

include excerpts of this seventeen page letter in this book? What does it

accomplish?

(6) Consider for a moment that the

letter might be made-up, a work of fiction. Why include it then?

(7) In "Notes," Tim O'Brien

says, "You start sometimes with an incident that truly happened, like the

night in the shit field, and you carry it forward by inventing incidents that

did not in fact occur but that nonetheless help to clarify and explain

it." What does this tell you about O'Brien's understanding of the way

fiction relates to real life?

Compare and contrast possible

versions of Kiowa's death in Speaking of Courage and the end of

"Notes". Who is responsible?

Wednesday, September 23, 2015

Style, Speaking of Courage and Notes

Driving through Minnesota During the Hanoi Bombings

BY ROBERT BLY

We drive between lakes just turning green;

Late June. The white turkeys have been moved

A second time to new grass.

How long the seconds are in great pain!

Terror just before death,

Shoulders torn, shot

From helicopters. “I saw the boy

being tortured with a telephone generator,”

The sergeant said.

“I felt sorry for him

And blew his head off with a shotgun.”

These instants become crystals,

Particles

The grass cannot dissolve. Our own gaiety

Will end up

In Asia, and you will look down in your cup

And see

Black Starfighters.

Our own cities were the ones we wanted to bomb!

Therefore we will have to

Go far away

To atone

For the suffering of the stringy-chested

And the short rice-fed ones, quivering

In the helicopter like wild animals,

Shot in the chest, taken back to be questioned.

Robert Bly, "Driving through Minnesota during the Hanoi Bombings" from Selected Poems, published by HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 1967 and renewed 1995 by Robert Bly. Used by permission of Robert Bly.

Source: Selected Poems (HarperCollins Publishers Inc, 1986)

Source: Selected Poems (HarperCollins Publishers Inc, 1986)

Friday, September 18, 2015

The Man I Killed/Ambush

The Man I Killed/Ambush

Thematic Search--Things They Carried

Discuss in groups. Post a comment or write a group answer. Report out.

GROUP A:

Spark Notes analysis:

"O’Brien illustrates the ambiguity and complexity of Vietnam by alternating explicit references to beauty and gore. The butterfly and the tiny blue flowers he mentions show the mystery and suddenness of death in the face of pristine natural phenomena. O’Brien’s observations of his victim lying on the side of the road—his jaw in his throat and his upper lip gone—emphasize the unnaturalness of war amid nature. The contrast of images is an incredibly ironic one that suggests the tragedy of death amid so much beauty. However, the presence of the butterfly and the tiny blue flowers also suggests that life goes on even despite such unspeakable tragedy. After O’Brien killed the Vietnamese soldier, the flowers didn’t shrivel up, and the butterfly didn’t fly away. They stayed and found their home around the tragedy. In this way, like the STORY

of Curt Lemon’s death, “The Man I Killed” is a story about the beauty of life rather than the gruesomeness of death."

of Curt Lemon’s death, “The Man I Killed” is a story about the beauty of life rather than the gruesomeness of death."Find contrasting images of beauty and gore in the chapter. Do you agree with this analysis?

Where else in the novel do you find images of the beauty of life contrasted with the gruesomeness of death?

Group B:

Again, from Spark notes:

“The Man I Killed” sets up ideas that are addressed in “Ambush,” just as “The Things They Carried” sets up ideas that are addressed in “Love.” The refrains of “The Man I Killed,” such as “he was a short, slender man of about twenty,” are constant, adding to the continuity of the storytelling. Unlike “The Man I Killed,” which seems to take place in real time, “Ambush” is already a memory STORY

—one with perspective, history, and a sense of life’s continuation. As such, O’Brien uses his narrative to clear up some of the questions that we might have about the somewhat ambiguous version of the story in “The Man I Killed.” But O’Brien’s memory is crystal clear. He remembers how he lobbed the grenade and that it seemed to freeze in the air for a moment, perhaps indicating his momentary regret even before the explosion detonated. He has a clear vision of the man’s actual death that he probably could not have articulated so close to the occurrence. O’Brien’s simile about the man seeming to jerk upward, as though pulled by invisible wires, suggests that the actions of the men in Vietnam were not entirely voluntary. They were propelled by another power outside of them—the power of guilt and responsibility and impulse and regret.

—one with perspective, history, and a sense of life’s continuation. As such, O’Brien uses his narrative to clear up some of the questions that we might have about the somewhat ambiguous version of the story in “The Man I Killed.” But O’Brien’s memory is crystal clear. He remembers how he lobbed the grenade and that it seemed to freeze in the air for a moment, perhaps indicating his momentary regret even before the explosion detonated. He has a clear vision of the man’s actual death that he probably could not have articulated so close to the occurrence. O’Brien’s simile about the man seeming to jerk upward, as though pulled by invisible wires, suggests that the actions of the men in Vietnam were not entirely voluntary. They were propelled by another power outside of them—the power of guilt and responsibility and impulse and regret.Where else in the novel do you find references to the power of guilt , responsibility and regret?

Group 3 Tim O'Brien discussing "Ambush":

Male audience member (Frank Grzyb): Hello? I've read several of your BOOKS

, and very curious about how much is real and how much isn't real. That's the first question. I find a lot to be real; you may have a different answer. The second question is I read a story that I find highly improbable, but it could be factual, knowing how weird Vietnam was, and that was, basically, about a guy who called and got his girlfriend to come into country, and she ended up in a Green Beret outfit, and I said, this could never happen, but Vietnam was so strange, it was liable to happen.

, and very curious about how much is real and how much isn't real. That's the first question. I find a lot to be real; you may have a different answer. The second question is I read a story that I find highly improbable, but it could be factual, knowing how weird Vietnam was, and that was, basically, about a guy who called and got his girlfriend to come into country, and she ended up in a Green Beret outfit, and I said, this could never happen, but Vietnam was so strange, it was liable to happen. Tim O'Brien: Yeah. Well, I'll respond in two ways. One - excuse me, my cold is hitting me now - (coughs) Excuse me. Number one, uh, the literal truth is ultimately, to me, irrelevant. What matters to me is the heart-truth. I'm going to die, you're all going to die, the earth is going to flame out when the sun goes. We all know the facts. The truth - I mean, does it matter what the real Hamlet was like, or the real Ulysses - does it matter? Well, I don't think so. In the fundamental human way, the ways we think about in our dream-lives, and our moral lives, and our spiritual lives, what matters is what happens in our hearts. A good lie, if nobly told, for good reason, seems to me preferable to a very boring and pedestrian truth, which can lie, too. That's one way of answering.

I'll give you a more practical answer. The last piece I read for you, it is very, and it does approximate an event that happened in my life, and it's hard for me to read to you, at the same time it wasn't literally true in all its detail. It wasn't a hand grenade, it was a, was a rifle thing. We had circled the village one night - called it cordoning the village - and this stuff never worked in Vietnam-those vets who are here know what I'm talking about-these things never worked, but it did, once. We circled the village and we drove the enemy out in daylight, and three enemy soldiers came marching-the silhouettes like you're at a carnival shoot - and about eighteen of us or twenty of us were lined up along a paddy dike. We all opened up from, I don't know, eighteen yards or twenty yards away. We, really, we killed one of them; the others we couldn't find, which shows you what bad shots we were on top of everything else. Well, I will never know whether I killed anyone, that man in particular - how do I know? I hope I didn't. But I'll never know.

The thing is, you have to, though, when you return from a war, you have to assume responsibility. I was there, I took part in it, I did pull the trigger, and whether I literally killed a man or not is finally irrelevant to me. What matters is I was part of it all, the machine that did it, and do feel a sense of obligation, and through that story I can share some of my feelings, when I walked over that corpse that day, and looked down at it, wondering, thinking, "dear God, dear God, please don't let it have been my bullet, Dear God, please." Um, that's the second answer.

What does this reveal about the purpose of these two stories-- "The Man I Killed" and "Ambush"-- in the novel?

How to Tell a True War Story/ Rhetorical Strategies

AGENDA :

Quiz #2 Literary Terms and Vocabulary

Review Prezi

Topic Tracking

HMWK: Read "The Man I Killed" and "Ambush" for Monday

Quiz #2 Literary Terms and Vocabulary

Review Prezi

Topic Tracking

HMWK: Read "The Man I Killed" and "Ambush" for Monday

Wednesday, September 16, 2015

Magic Realism and The Sweetheart of the Song Tra Bong

AGENDA:

Characteristics of Magical Realism

Hybridity—Magical realists incorporate many techniques that have been linked to post-colonialism, with hybridity being a primary feature. Specifically, magical realism is illustrated in the inharmonious arenas of such opposites as urban and rural, and Western and indigenous. The plots of magical realist works involve issues of borders, mixing, and change. Authors establish these plots to reveal a crucial purpose of magical realism: a more deep and true reality than conventional realist techniques would illustrate.

Irony Regarding Author’s Perspective—The writer must have ironic distance from the magical world view for the realism not to be compromised. Simultaneously, the writer must strongly respect the magic, or else the magic dissolves into simple folk belief or complete fantasy, split from the real instead of synchronized with it. The term "magic" relates to the fact that the point of view that the text depicts explicitly is not adopted according to the implied world view of the author. As Gonzales Echevarria expresses, the act of distancing oneself from the beliefs held by a certain social group makes it impossible to be thought of as a representative of that society.

Authorial Reticence—Authorial reticence refers to the lack of clear opinions about the accuracy of events and the credibility of the world views expressed by the characters in the text. This technique promotes acceptance in magical realism. In magical realism, the simple act of explaining the supernatural would eradicate its position of equality regarding a person’s conventional view of reality. Because it would then be less valid, the supernatural world would be discarded as false testimony.

The Supernatural and Natural—In magical realism, the supernatural is not displayed as questionable. While the reader realizes that the rational and irrational are opposite and conflicting polarities, they are not disconcerted because the supernatural is integrated within the norms of perception of the narrator and characters in the fictional world.

english.emory.edu/Bahri/MagicalRealism.html

DISCUSSION GROUPS:

HMWK: POST A COMMENT TO THE INTERPRETIVE QUESTIONS Level 2 and Allegorical/Symbolic Question Level 3

"The Sweetheart of the Song Tra Bong"

Level 2: Interpretive questions.

In "Sweetheart of the Song Tra Bong," what transforms Mary Anne into a predatory killer? Does it matter that Mary Anne is a woman? How so? What does the story tell us about the nature of the Vietnam War?

2. The story Rat tells in "Sweetheart of the Song Tra Bong" is highly fantastical. Does its lack of believability make it any less compelling? Do you believe it? Does it fit O'Brien's criteria for a true war story?

Level 3 Allegorical/Symbolic Questions What does this short story tell the reader about the nature of humanity? About war?

Basic Level I Reading Comprehension Questions

1. What was Rat’s reputation among the men of Alpha Company, when it came to telling stories?

2. What does Rat insist about his story in this chapter?

3. What was the military discipline like at the outpost?

4. Who were the Greenies and what were they like?

5. Who did Mark Fossie bring to the outpost?

6. What was their plan together, since elementary school?

7. What does Rat say are the similarities between Mary Ann and all of them?.

8. What did Mary Anne begin to do when casualties came in?

9. Where had Mary Anne been the first time she stayed out all night?

10. How did she change as a result of her conversation with Fossie the next morning?

11. How did she respond to Fossie’s arrangements to send her home?

12. When and under what circumstances did Rat see her next?

13. On pg. 106, what is Mitchell Sanders’ attitude about Rat’s way of telling a story?

14. What does Rat have to say about the soldiers attitude toward women?

15. What did the Rat, Fossie, and Eddie find when they entered the Greenies hootch?

16. What kind of jewelry was Mary Anne wearing?

17. What does Mary Anne tell Fossie about his presence in Vietnam?

18. What does Mary Anne say she wants to wants to do with Vietnam?

19. At the bottom of pg. 113, what does Rat say about "the girls back home"?

20. What is the metaphor that Rat uses to explain Mary Anne’s experience with war

Magic Realism and The Sweetheart of Song Tra Bong

Video: A Soldier's Sweetheart: http://vimeo.com/92513861

Magic Realism

A narrative technique that blurs the distinction between fantasy and reality. It is characterized by an equal acceptance of the ordinary and the extraordinary. Magic realism fuses (1) lyrical and, at times, fantastic writing with (2) an examination of the character of human existence and (3) an implicit criticism of society, particularly the elite."My most important problem was destroying

the lines of demarcation that separates what

seems real from what seems fantastic"

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez

Characteristics of Magical Realism

Hybridity—Magical realists incorporate many techniques that have been linked to post-colonialism, with hybridity being a primary feature. Specifically, magical realism is illustrated in the inharmonious arenas of such opposites as urban and rural, and Western and indigenous. The plots of magical realist works involve issues of borders, mixing, and change. Authors establish these plots to reveal a crucial purpose of magical realism: a more deep and true reality than conventional realist techniques would illustrate.

Irony Regarding Author’s Perspective—The writer must have ironic distance from the magical world view for the realism not to be compromised. Simultaneously, the writer must strongly respect the magic, or else the magic dissolves into simple folk belief or complete fantasy, split from the real instead of synchronized with it. The term "magic" relates to the fact that the point of view that the text depicts explicitly is not adopted according to the implied world view of the author. As Gonzales Echevarria expresses, the act of distancing oneself from the beliefs held by a certain social group makes it impossible to be thought of as a representative of that society.

Authorial Reticence—Authorial reticence refers to the lack of clear opinions about the accuracy of events and the credibility of the world views expressed by the characters in the text. This technique promotes acceptance in magical realism. In magical realism, the simple act of explaining the supernatural would eradicate its position of equality regarding a person’s conventional view of reality. Because it would then be less valid, the supernatural world would be discarded as false testimony.

The Supernatural and Natural—In magical realism, the supernatural is not displayed as questionable. While the reader realizes that the rational and irrational are opposite and conflicting polarities, they are not disconcerted because the supernatural is integrated within the norms of perception of the narrator and characters in the fictional world.

english.emory.edu/Bahri/MagicalRealism.html

DISCUSSION GROUPS:

HMWK: POST A COMMENT TO THE INTERPRETIVE QUESTIONS Level 2 and Allegorical/Symbolic Question Level 3

"The Sweetheart of the Song Tra Bong"

Level 2: Interpretive questions.

In "Sweetheart of the Song Tra Bong," what transforms Mary Anne into a predatory killer? Does it matter that Mary Anne is a woman? How so? What does the story tell us about the nature of the Vietnam War?

2. The story Rat tells in "Sweetheart of the Song Tra Bong" is highly fantastical. Does its lack of believability make it any less compelling? Do you believe it? Does it fit O'Brien's criteria for a true war story?

3. Find three symbols in this chapter and

explain them.

4.

Find three specific quotes and scenes

from the chapter that illustrate Mary Anne’s change. Also, explain Mary

Anne’s transformation. Does she go crazy? Or does she simply change?

5. Explain the whole “cave scene”. What is going on? What

has Mary Anne become? Make a list of all of

graphic imagery from that scene.

6.

Does it matter what happened, in the end, to Mary Anne? Would this be a better

story if we knew, precisely, what happened to her after she left camp? Or does

this vague ending add to the story? Either way, why?

Level 3 Allegorical/Symbolic Questions What does this short story tell the reader about the nature of humanity? About war?

Basic Level I Reading Comprehension Questions

1. What was Rat’s reputation among the men of Alpha Company, when it came to telling stories?

2. What does Rat insist about his story in this chapter?

3. What was the military discipline like at the outpost?

4. Who were the Greenies and what were they like?

5. Who did Mark Fossie bring to the outpost?

6. What was their plan together, since elementary school?

7. What does Rat say are the similarities between Mary Ann and all of them?.

8. What did Mary Anne begin to do when casualties came in?

9. Where had Mary Anne been the first time she stayed out all night?

10. How did she change as a result of her conversation with Fossie the next morning?

11. How did she respond to Fossie’s arrangements to send her home?

12. When and under what circumstances did Rat see her next?

13. On pg. 106, what is Mitchell Sanders’ attitude about Rat’s way of telling a story?

14. What does Rat have to say about the soldiers attitude toward women?

15. What did the Rat, Fossie, and Eddie find when they entered the Greenies hootch?

16. What kind of jewelry was Mary Anne wearing?

17. What does Mary Anne tell Fossie about his presence in Vietnam?

18. What does Mary Anne say she wants to wants to do with Vietnam?

19. At the bottom of pg. 113, what does Rat say about "the girls back home"?

20. What is the metaphor that Rat uses to explain Mary Anne’s experience with war

Epigraphs

Epigraph John Ransom

1. There is an epigraph at the beginning of the text. What is an

epigraph? How do writers use them? This epigraph is a citation from John

Ransom's Andersonville Diary. Who was he? What was Andersonville? Who

"wrote" or "edited" the Diary? Given what you discover about the

epigraph and what it introduces, what do you think it accomplishes?

John L. Ransom was born in

1843. He joined the Union Army

during the American

Civil War in November 1862 and served as Quartermaster of Company A, 9th

Michigan Volunteer Cavalry.

In 1863 Ransom was captured

in Tennessee and taken to Andersonville,

Georgia. During his imprisonment he kept a diary of his experiences. On the 6th

July, 1864 he wrote: "Boiling hot, camp reeking with filth, and no

sanitary privileges; men dying off over 140 per day. Stockade enlarged, taking

in eight or ten more acres, giving us more room, and stumps to dig up for wood

to cook with. Jimmy Devers has been a prisoner over a year and, poor boy, will

probably die soon. Have more mementos than I can carry, from those who have

died, to be given to their friends at home. At least a dozen have given me

letters, pictures, etc., to take North."

The Confederate authorities

did not provide enough food for the prison and men began to die of starvation.

The water became polluted and disease was a constant problem. Of the 49,485

prisoners who entered the camp, nearly 13,000 died from disease and

malnutrition.

In August, 1865 President Andrew Johnson give his approval for Henry Wirz, the commandant of Andersonville, to be charged with "wanton cruelty". Wirz appeared before a military commission headed by Major General Lew Wallace on 21st August, 1865.

Wirz was found guilty on 6th November and sentenced to death. He was taken to Washington to be executed in the same yard where those involved in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln had died. Alexander Gardner, the famous photographer, was invited to record the event. The execution took place on the 10th November. The gallows were surrounded by Union Army soldiers who throughout the procedure chanted "Wirz, remember, Andersonville."

John L. Ransom's book, Andersonville Diary, was published in 1881. He died at the age 76 years on 23rd September 1919 in Los Angeles County.

In August, 1865 President Andrew Johnson give his approval for Henry Wirz, the commandant of Andersonville, to be charged with "wanton cruelty". Wirz appeared before a military commission headed by Major General Lew Wallace on 21st August, 1865.

Wirz was found guilty on 6th November and sentenced to death. He was taken to Washington to be executed in the same yard where those involved in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln had died. Alexander Gardner, the famous photographer, was invited to record the event. The execution took place on the 10th November. The gallows were surrounded by Union Army soldiers who throughout the procedure chanted "Wirz, remember, Andersonville."

John L. Ransom's book, Andersonville Diary, was published in 1881. He died at the age 76 years on 23rd September 1919 in Los Angeles County.

(1) John L. Ransom, Andersonville

Diary (July, 1864)

6th July: Boiling hot, camp reeking with filth, and no sanitary privileges; men dying off over 140 per day. Stockade enlarged, taking in eight or ten more acres, giving us more room, and stumps to dig up for wood to cook with. Jimmy Devers has been a prisoner over a year and, poor boy, will probably die soon. Have more mementos than I can carry, from those who have died, to be given to their friends at home. At least a dozen have given me letters, pictures, etc., to take North. Hope I shan't have to turn them over to someone else.

7th July: Having formed a habit of going to sleep as soon as the air got cooled off and before fairly dark. I wake up at 2 or 3 o'clock and stay awake. I then take in all the horrors of the situation. Thousands are groaning, moaning, and crying, with no bustle of the daytime to drown it.

9th July: One-half the men here would get well if they only had something in the vegetable line to eat. Scurvy is about the most loathsome disease, and when dropsy takes hold with the scurvy, it is terrible. I have both diseases but keep them in check, and it only grows worse slowly. My legs are swollen, but the cords are not contracted much, and I can still walk very well.

10th July: Have bought (from a new prisoner) a large blank book so as to continue my diary. Although it is a tedious and tiresome task, am determined to keep it up. Don't know of another man in prison who is doing likewise. Wish I had the gift of description that I might describe this place.

Nothing can be worse kind of water. Nothing can be worse or nastier than the stream drizzling its way through this camp. And for air to breathe, it is what arises from this foul place. On al four sides of us are high walls and tall tress, and there is apparently no wind or breeze to blow away the stench, and we are obliged to breathe and live in it. Dead bodies lay around all day in the broiling sun, by the dozen and even hundreds, and we must suffer and live in this atmosphere.

12th July: I keep thinking our situation can get no worse, but it does get worse every day, and not less than 160 die each twenty-four hours. Probably one-forth or one-third of these die inside the stockade, the balance in the hospital outside. All day and up to 4 o'clock p.m., the dead are being gathered up and carried to the south gate and placed in a row inside the dead line. As the bodies are stripped of their clothing, in most cases as soon as the breath leaves and in some cases before, the row of dead presents a sickening appearance.

At 4 o'clock, a four or six mule wagon comes up to the gate, and twenty or thirty bodies are loaded onto the wagon and they are carried off to be put in trenches, one hundred in each trench, in the cemetery. It is the orders to attach the name, company, and regiment to each body, but it is not always done. My digging days are over. It is with difficulty now that I can walk, and only with the help of two canes.

6th July: Boiling hot, camp reeking with filth, and no sanitary privileges; men dying off over 140 per day. Stockade enlarged, taking in eight or ten more acres, giving us more room, and stumps to dig up for wood to cook with. Jimmy Devers has been a prisoner over a year and, poor boy, will probably die soon. Have more mementos than I can carry, from those who have died, to be given to their friends at home. At least a dozen have given me letters, pictures, etc., to take North. Hope I shan't have to turn them over to someone else.

7th July: Having formed a habit of going to sleep as soon as the air got cooled off and before fairly dark. I wake up at 2 or 3 o'clock and stay awake. I then take in all the horrors of the situation. Thousands are groaning, moaning, and crying, with no bustle of the daytime to drown it.

9th July: One-half the men here would get well if they only had something in the vegetable line to eat. Scurvy is about the most loathsome disease, and when dropsy takes hold with the scurvy, it is terrible. I have both diseases but keep them in check, and it only grows worse slowly. My legs are swollen, but the cords are not contracted much, and I can still walk very well.

10th July: Have bought (from a new prisoner) a large blank book so as to continue my diary. Although it is a tedious and tiresome task, am determined to keep it up. Don't know of another man in prison who is doing likewise. Wish I had the gift of description that I might describe this place.

Nothing can be worse kind of water. Nothing can be worse or nastier than the stream drizzling its way through this camp. And for air to breathe, it is what arises from this foul place. On al four sides of us are high walls and tall tress, and there is apparently no wind or breeze to blow away the stench, and we are obliged to breathe and live in it. Dead bodies lay around all day in the broiling sun, by the dozen and even hundreds, and we must suffer and live in this atmosphere.

12th July: I keep thinking our situation can get no worse, but it does get worse every day, and not less than 160 die each twenty-four hours. Probably one-forth or one-third of these die inside the stockade, the balance in the hospital outside. All day and up to 4 o'clock p.m., the dead are being gathered up and carried to the south gate and placed in a row inside the dead line. As the bodies are stripped of their clothing, in most cases as soon as the breath leaves and in some cases before, the row of dead presents a sickening appearance.

At 4 o'clock, a four or six mule wagon comes up to the gate, and twenty or thirty bodies are loaded onto the wagon and they are carried off to be put in trenches, one hundred in each trench, in the cemetery. It is the orders to attach the name, company, and regiment to each body, but it is not always done. My digging days are over. It is with difficulty now that I can walk, and only with the help of two canes.

(2) Some captured Union Army prisoners in Andersonville began stealing from fellow inmates. Henry Wirz gave instructions for the men to be arrested

and tried. John L. Ransom recorded in his diary how six of the men were

executed.

This morning, lumber was brought into the prison by the Rebels, and near the gate a gallows erected for the purpose of executing the six condemned Yankees. At about 10 o'clock they were brought inside by Captain Wirtz and some guards. Wirtz then said a few words about their having been tried by our own men and for us to do as we choose with them. I have learned by inquiry their names, which are as follows: John Sarsfield, 144th New York; William Collins, 88th Pennsylvania; Charles Curtiss, 5th Rhode Island Artillery; Pat Delaney, 83rd Pennsylvania; A. Munn, U.S. Navy and W.R. Rickson of the U.S. Navy.

All were given a chance to talk. Munn, a good-looking fellow in Marine dress, said he came into the prison four months before, perfectly honest and as innocent of crime as any fellow in it. Starvation, with evil companions, had made him what he was. He spoke of his mother and sisters in New York, that he cared nothing as far as he himself was concerned, but the news that would be carried home to his people made him want to curse God he had ever been born.

Delaney said he would rather be hung than live here as the most of them lived on the allowance of rations. If allowed to steal could get enough to eat, but as that was stopped had rather hang. He said his name was not Delaney and that no one knew who he really was, therefore his friends would never know his fate, his Andersonville history dying with him.

Curtiss said he didn't care a damn only hurry up and not be talking about it all day; making too much fuss over a very small matter. William Collins said he was innocent of murder and ought not be hung; he had stolen blankets and rations to preserve his own life, and begged the crowd not to see him hung as he had a wife and child at home.

Collins, although he said he had never killed anyone, and I don't believe he ever did deliberately kill a man, such as stabbing or pounding a victim to death, yet he has walked up to a poor sick prisoner on a cold night and robbed him of blanket, or perhaps his rations, and if necessary using all the force necessary to do it. These things were the same as life to the sick man, for he would invariably die.

Sarsfield made quite a speech; he had studied for a lawyer; at the outbreak of the rebellion he had enlisted and served three years in the army, being wounded in battle. Promoted to first sergeant and also commissioned as a lieutenant. He began by stealing parts of rations, gradually becoming hardened as he became familiar with the crimes practised; evil associates had helped him to go downhill.

At about 11 o'clock, they were all blindfolded, hands and feet tied, told to get ready, nooses adjusted, and the plank knocked from under. Munn died easily, as also did Delaney; all the rest died hard, and particularly Sarsfield, who drew his knees nearly to his chin and then straightened them out with a jerk, the veins in his neck swelling out as if they would burst.

Collins' rope broke and he fell to the ground, with blood spurting from his ears, mouth and nose. As they was lifting him back to the swinging-off place, he revived and begged for his life, but no use, was soon dangling with the rest, and died hard.

This morning, lumber was brought into the prison by the Rebels, and near the gate a gallows erected for the purpose of executing the six condemned Yankees. At about 10 o'clock they were brought inside by Captain Wirtz and some guards. Wirtz then said a few words about their having been tried by our own men and for us to do as we choose with them. I have learned by inquiry their names, which are as follows: John Sarsfield, 144th New York; William Collins, 88th Pennsylvania; Charles Curtiss, 5th Rhode Island Artillery; Pat Delaney, 83rd Pennsylvania; A. Munn, U.S. Navy and W.R. Rickson of the U.S. Navy.

All were given a chance to talk. Munn, a good-looking fellow in Marine dress, said he came into the prison four months before, perfectly honest and as innocent of crime as any fellow in it. Starvation, with evil companions, had made him what he was. He spoke of his mother and sisters in New York, that he cared nothing as far as he himself was concerned, but the news that would be carried home to his people made him want to curse God he had ever been born.

Delaney said he would rather be hung than live here as the most of them lived on the allowance of rations. If allowed to steal could get enough to eat, but as that was stopped had rather hang. He said his name was not Delaney and that no one knew who he really was, therefore his friends would never know his fate, his Andersonville history dying with him.

Curtiss said he didn't care a damn only hurry up and not be talking about it all day; making too much fuss over a very small matter. William Collins said he was innocent of murder and ought not be hung; he had stolen blankets and rations to preserve his own life, and begged the crowd not to see him hung as he had a wife and child at home.

Collins, although he said he had never killed anyone, and I don't believe he ever did deliberately kill a man, such as stabbing or pounding a victim to death, yet he has walked up to a poor sick prisoner on a cold night and robbed him of blanket, or perhaps his rations, and if necessary using all the force necessary to do it. These things were the same as life to the sick man, for he would invariably die.

Sarsfield made quite a speech; he had studied for a lawyer; at the outbreak of the rebellion he had enlisted and served three years in the army, being wounded in battle. Promoted to first sergeant and also commissioned as a lieutenant. He began by stealing parts of rations, gradually becoming hardened as he became familiar with the crimes practised; evil associates had helped him to go downhill.

At about 11 o'clock, they were all blindfolded, hands and feet tied, told to get ready, nooses adjusted, and the plank knocked from under. Munn died easily, as also did Delaney; all the rest died hard, and particularly Sarsfield, who drew his knees nearly to his chin and then straightened them out with a jerk, the veins in his neck swelling out as if they would burst.

Collins' rope broke and he fell to the ground, with blood spurting from his ears, mouth and nose. As they was lifting him back to the swinging-off place, he revived and begged for his life, but no use, was soon dangling with the rest, and died hard.

Tuesday, September 15, 2015

Postmodernism/Metafiction

AGENDA:

EQ:What is postmodernism?

The term Postmodern literature is used to describe certain tendencies in post-World War II literature. It is both a continuation of the experimentation championed by writers of the modernist period (relying heavily, for example, on fragmentation, paradox, questionable narrators, etc.) and a reaction against Enlightenment ideas implicit in Modernist literature. Postmodern literature, like postmodernism as a whole, is hard to define and there is little agreement on the exact characteristics, scope, and importance of postmodern literature. However, unifying features often coincide with Jean-François Lyotard's concept of the "meta-narrative" and "little narrative," Jacques Derrida's concept of "play," and Jean Baudrillard's "simulacra." For example, instead of the modernist quest for meaning in a chaotic world, the postmodern author eschews, often playfully, the possibility of meaning, and the postmodern novel is often a parody of this quest. This distrust of totalizing mechanisms extends even to the author; thus postmodern writers often celebrate chance over craft and employ metafiction to undermine the author's "univocal" control (the control of only one voice). The distinction between high and low culture is also attacked with the employment of pastiche, the combination of multiple cultural elements including subjects and genres not previously deemed fit for literature. A list of postmodern authors often varies; the following are some names of authors often so classified, most of them belonging to the generation born in the interwar period: William Burroughs (1914-1997), Alexander Trocchi (1925-1984), Kurt Vonnegut (1922-2007), John Barth (b. 1930), Donald Barthelme (1931-1989), E. L. Doctorow (b. 1931), Robert Coover (1932), Jerzy Kosinski (1933-1991) Don DeLillo (b. 1936), Thomas Pynchon (b. 1937), Ishmael Reed (1938), Kathy Acker (1947-1997), Paul Auster (b. 1947)[1], Orhan Pamuk (b. 1952).

Metafiction is a type of fiction that self-consciously addresses

the devices of fiction, exposing the fictional illusion. It is the

literary term describing fictional writing that self-consciously and

systematically draws attention to its status as an artifact in posing

questions about the relationship between fiction and reality, usually

using irony and self-reflection. It can be compared to presentational

theatre, which does not let the audience forget it is viewing a play;

metafiction does not let the reader forget he or she is reading a

fictional work.

Metafiction is primarily associated with Modernist and Postmodernist literature, but is found at least as early as the 9th-century One Thousand and One Nights and Chaucer's 14th-century Canterbury Tales. Cervantes' Don Quixote is a metafictional novel, as is James Hogg's The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824). In the 1950s several French novelists published works whose styles were collectively dubbed "nouveau roman". These "new novels" were characterized by their bending of genre and style and often included elements of metafiction. It became prominent in the 1960s, with authors and works such as John Barth's Lost in the Funhouse, Robert Coover's The Babysitter and The Magic Poker, Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse Five, Thomas Pynchon's The Crying of Lot 49 and William H. Gass's Willie Master's Lonesome Wife. William H. Gass coined the term “metafiction” in a 1970 essay entitled “Philosophy and the Form of Fiction”. Unlike the antinovel, or anti-fiction, metafiction is specifically fiction about fiction, i.e. fiction which self-consciously reflects upon itself

How to Tell a True War Story

AGENDA:

Continue discussion from yesterday

Videos

Platoon: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pPi8EQzJ2Bg

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mKpQB3bEPbI&list=TLpkj93aMlKiM

Tim O'Brien:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C48fWkljK28

http://prezi.com/i7pnwqaf45c2/the-things-they-carried-lesson-plan/

Read over the following summaries and analysis of "How to Tell a True War Story." Then discuss with your group the key questions posted in red. As a group find passages in the story that show the distinction between "happening truth" and "story truth". Post a group comment reflecting the key points of your discussion and passages you may want to refer to later in your paper. Why are ambiguity and paradox so important to the telling of these stories about the Vietnam War?

Memory and Reminiscence

Because ‘‘How to Tell a True War Story’’ is written by a Vietnam War veteran, and because Tim O’Brien has chosen to create a narrator with the same name as his own, most readers want to believe that the stories O’Brien tells are true and actually happened to him. There are several reasons for this. In the first place, O’Brien’s so-called memoir, If I Die In a Combat Zone, contains many stories that find their way into his later novels and short fiction. Thus, it is difficult for the reader to sort through what is memory and what is fiction.

There are those, however, who would suggest that this is one of O’Brien’s points in writing his stories. Although most readers would believe that their own memories are ‘‘true,’’ this particular story sets out to demonstrate the way that memories are at once true and made up.

Further, as O’Brien tells the reader in ‘‘How to Tell a True War Story,’’ ‘‘You’d feel cheated if it never happened.’’ This is certainly one response to O’Brien’s story. Readers want the stories to be true in the sense that they grow out of O’Brien’s memory. O’Brien, however, will not let the reader take this easy way out. Instead, he questions the entire notion of memoir, reminiscence, and the ability of memory to convey the truth.

Truth and Falsehood

Certainly, the most insistent theme in this story is that of truth and falsehood. O’Brien, however, would be unlikely to set up such a dichotomy. That is, according to ‘‘How to Tell a True War Story,’’ truth is not something that can find its opposition in untruth. Rather, according to O’Brien, because war is so ambiguous, truth takes on many guises. Even seemingly contradictory events can both be considered true. O’Brien uses the event of Curt Lemon’s death to make this point. O’Brien knows, for example, that Curt is killed by a rigged 105mm round. However, as the scene replays in his mind, O’Brien sees the event very differently. It seems to him that Curt is killed by the sunlight, and that it is the sunlight that lifts him high into the tree where O’Brien will later have to retrieve Curt’s body parts. Thus O’Brien distinguishes between the truth that happens and the truth that seems to happen.

Moreover, O’Brien likes to play with words and to undermine the logical connection between words. In Western philosophy, it is considered impossible for a word to mean itself and its opposite at the same time. O’Brien demonstrates it may indeed be possible. For example, when he writes, ‘‘it is safe to say that in a true war story nothing is ever absolutely true,’’ he is creating a paradox. If nothing is ever absolutely true, then even that statement cannot be absolutely true. The paradox suggests that while it might be possible to approximate truth, it must be told, as Emily Dickinson once wrote, ‘‘aslant.’’

Perhaps the most disconcerting moment in this tale occurs when O’Brien tells the story of the woman who approaches him after he tells this tale. Most readers assume that O’Brien the author is speaking, and that perhaps he is telling a story of what happened to him after a reading of his fiction. When the woman says she likes the story about the water buffalo, O’Brien is annoyed. Although he does not tell her, he tells the reader that the entire episode did not happen, that it was all made up, and that even the characters are not real.

Readers may be shocked. How could O’Brien have fabricated all of this? Then the reader may realize that O’Brien is playing with the truth again, for if everything in the story is fabricated, then so is the woman who approached him. This play with truth and falsehood provides both delight and despair for the reader who will never be able to determine either truth or falsehood in O’Brien’s stories in the traditional sense. As Stephen Kaplan suggests in Understanding Tim O’Brien, ‘‘[O’Brien] completely destroys the fine line dividing fact from fiction and tries to show . . . that fiction (or the imagined world) can often be truer, especially in the case of Vietnam, than fact.’’

How to Tell a True War Story: Style

Point of View and Narration

One of the most interesting, and perhaps troubling, aspects of the construction of ‘‘How to Tell a True War Story’’ is O’Brien’s choice to create a fictional, first-person narrator who also carries the name ‘‘Tim O’Brien.’’ Although the narrator remains unnamed in this particular story, other stories in the collection clearly identify the narrator by the name Tim. Further, the other stories in the collection also identify the narrator as a forty-three-yearold writer who writes about the Vietnam War, ever more closely identifying the narrator with the author.

On the one hand, this connection is very compelling. Readers are drawn into the story believing that they are reading something that has some basis in the truth of the writer Tim O’Brien. Further, the authorial voice that links the story fragments together sounds like it ought to belong to the writer.

On the other hand, however, the device allows O’Brien to play with notions of truth and ambiguity. Does the narrator represent the author? Or do the narrator’s words tell the reader not to trust either the story or the teller? What can be said unequivocally about the Vietnam War? O’Brien’s use of the fictional narrator

suggests that there is nothing unequivocal about the war. Rather, it seems that O’Brien, through his narrator Tim, wants the reader to understand that during war, seeming-truth can be as true as happening-truth.

Ought the reader consider the narrator to be unreliable? After all, after pledging the truth of the story from the very first line, he undercuts that claim by telling the reader at the last possible moment that none of the events in the story happened. While this might seem to point to an unreliable narrator, a narrator who cannot find it in himself to tell the truth, it is more likely that O’Brien is making the point that the entire story is true, it just never happened. This distinction, while frustrating for some readers, is an important one not only for the understanding of ‘‘How to Tell a True War Story’’ but also for the reading of The Things They Carried. Structure

‘‘How to Tell a True War Story’’ is not structured in a traditional manner, with a sequential narrative that moves chronologically from start to finish. Rather, O’Brien has chosen to use a number of very short stories within the body of the full story to illustrate or provide examples of commentary provided by the narrator.

That is, the narrator will make some comment about the nature of a ‘‘true’’ war story, then will recount a brief story that illustrates the point. These stories within the larger story are not arranged chronologically.

Consequently, the reader learns gradually, and out of sequence, the events that led to the death of Curt Lemon as well as the events that take place after his death.

This structure serves two purposes. In the first place, the structure allows the story to move back and forth between concrete image and abstract reality. The narrator writes that ‘‘True war stories do not generalize.

They do not indulge in abstraction or analysis.’’ Thus, for the narrator to provide ‘‘true’’ war stories, he must provide the concrete illustration. While the stories within the larger story, then, may qualify as ‘‘true’’war stories, the larger story cannot, as it does indulge in abstraction and analysis.

The second purpose served by this back-and forth structure is that it mirrors and reflects the structure of the book The Things They Carried. Just as the story has concrete, image-filled stories within it, so too does the larger book contain chapters that are both concrete and image-filled. Likewise, there are chapters within the book that serve as commentary on the rest of the stories. As a result, ‘‘How to Tell a True War Story’’ provides for the reader a model of how the larger work functions.

The story that results from this metafictional (metafiction is fiction that deals with the writing of fiction or its conventions) structure may seem fragmentary because of the many snippets of the story that find their way into the narrative. However, the metafictional commentary provided by the narrator binds the stories together just as the chapters of the book are bound together by the many linkages O’Brien provides.

Tim O’Brien’s Criteria:

o A true war story is never moral.

o It does not instruct, nor encourage virtue, nor suggest models of proper human behavior, nor restrain men from doing the things men have always done.

o If a story seems moral, do not believe it.

o Does not uplift

o No virtue

o Allegiance to obscenity and evil

o Difficult to separate what happened from what seemed to happen

o Cannot be believed… must be at least skeptical.

o Often the crazy stuff is true and the normal stuff isn’t

o You can’t even tell it—it’s beyond telling.

o It never seems to end.

o If there’s a moral, it’s a tiny thread that makes the cloth, you can’t tease it out or find meaning without unraveling deeper meaning.

o You might have no more to say than maybe “oh.”

o Makes the stomach believe

o Does not generalize, abstract, analyze

o Nothing is ever absolutely true.

o Often there is not a point that hits you right away…

o Never about war.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)