AGENDA:

Work on poetry projects for presentation tomorrow

The AP English Language and Composition course is designed to enable students to become skilled readers and writers in diverse genres and modes of composition. As stated in the Advanced Placement Course Description, the purpose of the Language and Composition course is “to enable students to read complex texts with understanding and to write papers of sufficient richness and complexity to communicate effectively with mature readers” (The College Board, May 2007, May 2008, p.6).

Monday, March 23, 2015

Monday, March 16, 2015

Susan B. Anthony essay/Literature Circles, Day 2

AGENDA:

Review Susan B. Anthony essay

Continue Literature Circles throughout the week March 16-20

Due Date: March 24 Poetry projects

Link to Kaplan vocabulary:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-adv/eduadv/kaplan/kart_ug_sat100.html

Review Susan B. Anthony essay

Continue Literature Circles throughout the week March 16-20

Due Date: March 24 Poetry projects

Link to Kaplan vocabulary:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-adv/eduadv/kaplan/kart_ug_sat100.html

Friday, March 13, 2015

Literature Circles

AGENDA:

Quiz--Spelling, vocab, and short stories

Link to vocabulary: Kaplan's SAT 100

http://www.vocabulary.com/lists/228341

Work in literature circles throughout this week

Quiz--Spelling, vocab, and short stories

Link to vocabulary: Kaplan's SAT 100

http://www.vocabulary.com/lists/228341

Work in literature circles throughout this week

Wednesday, March 11, 2015

Blogging

AGENDA:

- Overview-Why Use Blogs in the Classroom?--Marcy

- Sharing of blogs- Brad Craddock, dolly Parker, Stephanie Lawson and others?

- Creating a New Blog or Adding to an Existing Blog

The Real Thing/

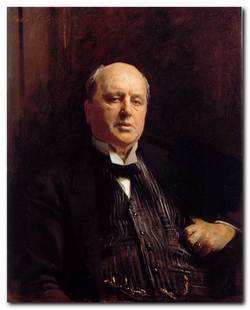

Henry James – portrait by John Singer Sargeant

Principal characters

|

The Real Thing – critical commentary

This is a very popular, well-known, and much reprinted tale – possibly because it is so short, so touching, and because it seems to offer an easy glimpse into the theories of art that James wrote about so obscurely in the famous ‘Prefaces’ to the New York edition of his collected works.Major and Mrs Monarch are truly pathetic figures. They are an upper-class ‘gentleman’ and ‘lady’ who have fallen on hard times after losing their money. They cling to their snobbish notions of class and status – yet they are virtually empty figures. The narrator conceives of them as the products of a purposeless, trite, and conventional lifestyle. They also naively believe that their sense of good manners and visual appeal are marketable commodities – but they are mistaken.

Their humiliating attempts to become useful to the narrator are given an excruciatingly ironic twist when they end up serving tea and acting as housekeepers – in place of the two lower-class figures of Miss Churm and Oronte, who successfully occupy the places as models the Monarchs were seeking.

At an artistic level, this is the ‘success’ of the tale. Major and Mrs Monarch think they are ‘the real thing’ as representatives of class types – and that they will be useful to the narrator in his work as an illustrator. But they lack plasticity; they can only ever be what they are – stuffed dummies with no character at all. Miss Churm and Oronte on the other hand are capable of becoming ‘suggestive’ for the narrator’s purposes, and are visually creative.

In other words, the story illustrates that a superficial appearance of being ‘the real thing’ is not sufficient to guarantee artistic success. The narrator’s drawings using the Monarchs as models are deemed a failure by his friend Jack Hawley and the publisher’s artistic director. But when he reverts to using Miss Churm and Oronte as models, he succeeds and gains the commission for the whole series of illustrated novels.

Tuesday, March 10, 2015

"The Real Thing" by Henry James

AGENDA:

With its ironic examination of the relationship between representations and reality, “The Real Thing” can serve as an excellent jumping-off point for a discussion of realism as an artistic movement. The story serves as a kind of fable about the artistic production of realistic representation. The reader, along with the artist in the story, comes to realize that it is precisely because the Monarchs represent British aristocratic values that they fail as models of the type. Artistic inspiration seems to depend on artificiality and pretense (figured by the lower-class models) and is hampered by the stifling presence of the “real thing.”

http://www.henryjames.org.uk/realth/RTtext.htm

With its ironic examination of the relationship between representations and reality, “The Real Thing” can serve as an excellent jumping-off point for a discussion of realism as an artistic movement. The story serves as a kind of fable about the artistic production of realistic representation. The reader, along with the artist in the story, comes to realize that it is precisely because the Monarchs represent British aristocratic values that they fail as models of the type. Artistic inspiration seems to depend on artificiality and pretense (figured by the lower-class models) and is hampered by the stifling presence of the “real thing.”

- Think about the implications of James’s fable about the making of realistic art.

- What is the relationship between the artist and reality?

- What seems to be the goal of the “realist” art object?

- What is the relationship between the artist in the story and Henry James, the writer?

http://www.henryjames.org.uk/realth/RTtext.htm

19th c. Writers--American Literature The Story of an Hour/The Yellow Wallpaper

AGENDA:

Yesterday we read "The Story of an Hour" by Kate Chopin. For homework, you read "The Yellow Wallpaper" which we will be discussing today in class.

For HMWK: Please read "The Real Thing" by Henry James

READING GROUPS: Please choose a novel to read and discuss in the next two weeks

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton

My Antonia by Willa Cather

The Awakening by Kate Chopin

Herland by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Miscellaneous Group: Daisy Miller and Turn of the Screw by Henry James,. Red Badge of Courage by Stephen Crane, etc.

Why I wrote the Yellow Wallpaper

“The Yellow Wallpaper” is an exaggerated account of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s personal experiences. In 1887, shortly after the birth of her daughter, Gilman began to suffer from serious depression and fatigue. She was referred to Silas Weir Mitchell, a leading specialist in women’s nervous disorders in the nineteenth century, who diagnosed Gilman with neurasthenia and prescribed a “rest cure” of forced inactivity. Weir Mitchell believed that nervous depression was a result of overactive nerves and ordered Gilman to cease all forms of creative activity, including writing, for the rest of her life. The goal of the treatment was to promote domesticity and calm her agitated nerves.Gilman attempted to endure the “rest cure” treatment and did not write or work for three months. Eventually, she felt herself beginning to go slowly insane from the inactivity and, at one point, was reduced to crawling under her bed holding a rag doll. Unlike the protagonist in her story, Gilman did not reach the point of total madness, but she knew that her deteriorating mental condition was due to the oppressive medical regime that was meant to “cure” her. She abandoned Mitchell’s advice and moved to California in order to overcome her depression on her own. Although Gilman’s attempt was successful, she claimed to suffer from post-traumatic stress from Weir Mitchell’s treatment for the rest of her life. In 1890, Gilman wrote “The Yellow Wallpaper” in an effort to save other women from suffering the same oppressive treatment. Weir Mitchell and his treatment play a key role in the narrative; in the third section of the text, the protagonist’s husband even threatens to send her to Weir Mitchell in the fall if she does not recover soon.

In 1890, Gilman sent the story to writer William Dean Howells, who submitted it to Horace Scudder, editor of the prestigious magazine, “The Atlantic Monthly.” Scudder rejected the story as depressing material, and returned it to Gilman with a handwritten note that read: “Dear Madam: W. Howells has handed me this story. I could not forgive myself if I made others as miserable as I have made myself! Sincerely Yours, H. E. Scudder.” Eventually the story was published in “The New England Magazine” in May 1892. According to Gilman’s autobiography, she sent a copy of “The Yellow Wallpaper” to Weir Mitchell after its publication. Although she never received a response, she claimed that Weir Mitchell later changed his official treatment for nervous depression as a direct result of her story. Gilman also asserted that she knew of one particular woman who had been spared the “rest cure” as a treatment for her depression after her family read “The Yellow Wallpaper.”

The public reaction to the story was strong, if mixed. In many circles, “The Yellow Wallpaper” was perceived as nothing more than a horror story, stemming from the gothic example of Edgar Allen Poe and Mary Shelley. It was not until the 1970s that the story was also recognized as a feminist narrative worthy of historical and literary scholarship.

-->

Yesterday we read "The Story of an Hour" by Kate Chopin. For homework, you read "The Yellow Wallpaper" which we will be discussing today in class.

For HMWK: Please read "The Real Thing" by Henry James

READING GROUPS: Please choose a novel to read and discuss in the next two weeks

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton

My Antonia by Willa Cather

The Awakening by Kate Chopin

Herland by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Miscellaneous Group: Daisy Miller and Turn of the Screw by Henry James,. Red Badge of Courage by Stephen Crane, etc.

Why I wrote the Yellow Wallpaper

“The Yellow Wallpaper” is an exaggerated account of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s personal experiences. In 1887, shortly after the birth of her daughter, Gilman began to suffer from serious depression and fatigue. She was referred to Silas Weir Mitchell, a leading specialist in women’s nervous disorders in the nineteenth century, who diagnosed Gilman with neurasthenia and prescribed a “rest cure” of forced inactivity. Weir Mitchell believed that nervous depression was a result of overactive nerves and ordered Gilman to cease all forms of creative activity, including writing, for the rest of her life. The goal of the treatment was to promote domesticity and calm her agitated nerves.Gilman attempted to endure the “rest cure” treatment and did not write or work for three months. Eventually, she felt herself beginning to go slowly insane from the inactivity and, at one point, was reduced to crawling under her bed holding a rag doll. Unlike the protagonist in her story, Gilman did not reach the point of total madness, but she knew that her deteriorating mental condition was due to the oppressive medical regime that was meant to “cure” her. She abandoned Mitchell’s advice and moved to California in order to overcome her depression on her own. Although Gilman’s attempt was successful, she claimed to suffer from post-traumatic stress from Weir Mitchell’s treatment for the rest of her life. In 1890, Gilman wrote “The Yellow Wallpaper” in an effort to save other women from suffering the same oppressive treatment. Weir Mitchell and his treatment play a key role in the narrative; in the third section of the text, the protagonist’s husband even threatens to send her to Weir Mitchell in the fall if she does not recover soon.

In 1890, Gilman sent the story to writer William Dean Howells, who submitted it to Horace Scudder, editor of the prestigious magazine, “The Atlantic Monthly.” Scudder rejected the story as depressing material, and returned it to Gilman with a handwritten note that read: “Dear Madam: W. Howells has handed me this story. I could not forgive myself if I made others as miserable as I have made myself! Sincerely Yours, H. E. Scudder.” Eventually the story was published in “The New England Magazine” in May 1892. According to Gilman’s autobiography, she sent a copy of “The Yellow Wallpaper” to Weir Mitchell after its publication. Although she never received a response, she claimed that Weir Mitchell later changed his official treatment for nervous depression as a direct result of her story. Gilman also asserted that she knew of one particular woman who had been spared the “rest cure” as a treatment for her depression after her family read “The Yellow Wallpaper.”

The public reaction to the story was strong, if mixed. In many circles, “The Yellow Wallpaper” was perceived as nothing more than a horror story, stemming from the gothic example of Edgar Allen Poe and Mary Shelley. It was not until the 1970s that the story was also recognized as a feminist narrative worthy of historical and literary scholarship.

Why I Wrote “The Yellow Wallpaper”

By Charlotte Perkins Gilman, as it appeared in The Forerunner, October 1913

Many and many a reader has asked that. When the story first came out, in the New England Magazine about 1891, a Boston physician made protest in The Transcript. Such a story ought not to be written, he said; it was enough to drive anyone mad to read it.

Another physician, in Kansas I think, wrote to say that it was the best description of incipient insanity he had ever seen, and, begging my pardon, had I been there?

Now the story of the story is this:

For many years I suffered from a severe and continuous nervous breakdown tending to melancholia and beyond. During about the third year of this trouble I went, in devout faith and some faint stir of hope, to a noted specialist in nervous diseases, the best known in the country. This wise man put me to bed and applied the rest cure, to which a still-good physique responded so promptly that he concluded there was nothing much the matter with me, and sent me home with solemn advice to “live as domestic life as far as possible,” to “have but two hours intellectual life a day,” and “never to touch pen, or pencil again” as long as I lived. This was in 1887.

I went home and obeyed those directions for some three months, and came so near the borderline of utter mental ruin that I could see over.

Then, using the remnants of intelligence that remained, and helped by a wise friend, I cast the noted specialist’s advice to the winds and went to work again – work, the normal life of every human being; work, in which is joy and growth and service, without which one is a pauper and a parasite – ultimately recovering some measure of power.

Being naturally moved to rejoicing by this narrow escape, I wrote, “The Yellow Wallpaper,” with its embellishments and additions, to carry out the ideal (I never had hallucinations or objections to my mural decorations) and sent a copy to the physician who so nearly drove me mad. He never acknowledged it.

The little book is valued by alienists and as a good specimen of one kind of literature. It has, to my knowledge, saved one woman from a similar fate so terrifying her family that they let her out into normal activity and she recovered.

But the best result is this. Many years later I was told that the great specialist had admitted to friends of his that he had altered his treatment of neurasthenia since reading “The Yellow Wallpaper.”

It was not intended to drive people crazy, but to save people from being driven crazy, and it worked.

With a partner or two: write your thoughts about each of the underlined words in the article by Gilman. If you don’t know what a word means (like neurasthenia) look it up!! Be prepared to share with the class.

Mad:

Incipient Insanity:

Nervous Breakdown:

Melancholia:

Nervous Diseases:

Mental Ruin:

Neurasthenia:

Crazy:

1. Discuss "The Yellow Wallpaper" by Charlotte Perkins Gillman

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gWJ4ZtLlRvE&list=PLA9B79A6592B5414C&index=2

If you are interested in watching the entire PBS Masterpiece Theater production, here is the link to the playlist on Youtube.

The Yellow Wallpaper

More information about "The Yellow Wallpaper"

http://faculty.georgetown.edu/bassr/heath/syllabuild/iguide/gilman.html

Gothic Genre: Defining GothicThe gothic novel dominated English literature during the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century. Often, architectural ruins, monasteries, forlorn characters, elements of the supernatural and overall feelings of melancholy and madness prevailed in gothic works. It seems likely that the gothic novel was a reaction to the increased disillusionment in Enlightenment thinking The gothic genre's bizarre images and obsessions with death, evil and mystery reflect a reaction to the age of reason, order and politics of nineteenth century England as well. A story of terror and suspense, gothic has also been defined as, " . . . a popular woman's romance dealing with endangered heroines."11 A more comprehensive definition can be found in A Glossary of Literary Terms. It states, " . . . the best of them opened up to fiction the realm of the irrational and of the perverse impulses and the nightmarish terrors that lie beneath the orderly surface of the civilized mind . . ." The gothic genre proves to be a favorite of high school students. Most students become fascinated with examinations of horror, the supernatural, psychology and the mind. Gothic works naturally generate psychological responses from readers, therefore motivating students to search for deeper meanings and a variety of analysis. Gothic Genre: The Female GothicEllen Moers is known for establishing the term "female gothic" as an element of literary analysis. According to Moers, female gothic refers to writings where " . . . fantasy predominates over reality, the strange over the commonplace, and the supernatural over the natural, with one definite auctorial intent: to scare".12 Gilman's story, "The Yellow Wallpaper" has been called gothic because of its focus on madness and its horrifying conclusion. Some critics even chose to compare Gilman's story to the stories of Edgar Allan Poe, because of its remarkable depiction of the deterioration of the human mind. In addition, Gilman's narrator's madness is focused on the wallpaper, serving a similar function to Poe's famous black cat or tell-tale heart. Almost 100 years before Gilman's story was published, Ann Radcliffe established a standard for a gothic novel written by a woman writer. Radcliffe's novel's central figure is a young woman who was a persecuted victim and courageous heroine. Applying this definition to "The Yellow Wallpaper," it is clear to see why the story has been called gothic. Further complicating the analysis of Gilman's story as a gothic tale is Moers' discussion of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. A novel about creation, birth and its traumatic aftermath, Shelley established fear, guilt, depression, and anxiety as commonplace reactions to birth. In real life, Gilman's own nervous condition followed the birth of her daughter, Katherine, and paralleled the narrator's madness which revolves around the yellow wallpaper of an old nursery. Unlike many some gothic tales, Gilman's story is not simply about a haunted environment or an estranged woman. The story connects both setting and character with a chilling effect.

1. Discuss "The Yellow Wallpaper" by Charlotte Perkins Gillman

- What did you think of the story? The main character?

- What was your impression/interpretation of the ending?

- What tenets of Freud or Jung could you find?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gWJ4ZtLlRvE&list=PLA9B79A6592B5414C&index=2

If you are interested in watching the entire PBS Masterpiece Theater production, here is the link to the playlist on Youtube.

The Yellow Wallpaper

More information about "The Yellow Wallpaper"

http://faculty.georgetown.edu/bassr/heath/syllabuild/iguide/gilman.html

Gothic Genre: Defining GothicThe gothic novel dominated English literature during the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century. Often, architectural ruins, monasteries, forlorn characters, elements of the supernatural and overall feelings of melancholy and madness prevailed in gothic works. It seems likely that the gothic novel was a reaction to the increased disillusionment in Enlightenment thinking The gothic genre's bizarre images and obsessions with death, evil and mystery reflect a reaction to the age of reason, order and politics of nineteenth century England as well. A story of terror and suspense, gothic has also been defined as, " . . . a popular woman's romance dealing with endangered heroines."11 A more comprehensive definition can be found in A Glossary of Literary Terms. It states, " . . . the best of them opened up to fiction the realm of the irrational and of the perverse impulses and the nightmarish terrors that lie beneath the orderly surface of the civilized mind . . ." The gothic genre proves to be a favorite of high school students. Most students become fascinated with examinations of horror, the supernatural, psychology and the mind. Gothic works naturally generate psychological responses from readers, therefore motivating students to search for deeper meanings and a variety of analysis. Gothic Genre: The Female GothicEllen Moers is known for establishing the term "female gothic" as an element of literary analysis. According to Moers, female gothic refers to writings where " . . . fantasy predominates over reality, the strange over the commonplace, and the supernatural over the natural, with one definite auctorial intent: to scare".12 Gilman's story, "The Yellow Wallpaper" has been called gothic because of its focus on madness and its horrifying conclusion. Some critics even chose to compare Gilman's story to the stories of Edgar Allan Poe, because of its remarkable depiction of the deterioration of the human mind. In addition, Gilman's narrator's madness is focused on the wallpaper, serving a similar function to Poe's famous black cat or tell-tale heart. Almost 100 years before Gilman's story was published, Ann Radcliffe established a standard for a gothic novel written by a woman writer. Radcliffe's novel's central figure is a young woman who was a persecuted victim and courageous heroine. Applying this definition to "The Yellow Wallpaper," it is clear to see why the story has been called gothic. Further complicating the analysis of Gilman's story as a gothic tale is Moers' discussion of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. A novel about creation, birth and its traumatic aftermath, Shelley established fear, guilt, depression, and anxiety as commonplace reactions to birth. In real life, Gilman's own nervous condition followed the birth of her daughter, Katherine, and paralleled the narrator's madness which revolves around the yellow wallpaper of an old nursery. Unlike many some gothic tales, Gilman's story is not simply about a haunted environment or an estranged woman. The story connects both setting and character with a chilling effect.

Friday, March 6, 2015

Twain's "Two Ways of Seeing a River"/ Chadwick's essay "Why Huck Finn Belongs in the Classroom"

AGENDA:

Thursday, 3/5

EQ: How do romantic and realistic approaches to DESCRIPTION contrast in Twain's essay?

Read and discuss Twain's "Two Ways of Seeing a River"

Work on HUCK FINN Study Guide--DUE tomorrow, Fri. 3/6

Friday, 3/6

AGENDA:

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS FOR THIS UNIT:

What is satire? What are the techniques satirists use? What is the difference between Horatian and Juvenalian satire

What are the characteristics of the realist period in American literature? How does it contrast with romanticism?

How does Mark Twain employ both kinds of satire in his essays and in his fiction--i.e. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn? What is the novel relevant for us today and why has it stirred so much controversy over the years?

Read and discuss Jocelyn Chadwick's essay.

View excerpts from Ken Burns' Mark Twain video for PBS

Thursday, 3/5

EQ: How do romantic and realistic approaches to DESCRIPTION contrast in Twain's essay?

Read and discuss Twain's "Two Ways of Seeing a River"

Work on HUCK FINN Study Guide--DUE tomorrow, Fri. 3/6

Friday, 3/6

AGENDA:

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS FOR THIS UNIT:

What is satire? What are the techniques satirists use? What is the difference between Horatian and Juvenalian satire

What are the characteristics of the realist period in American literature? How does it contrast with romanticism?

How does Mark Twain employ both kinds of satire in his essays and in his fiction--i.e. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn? What is the novel relevant for us today and why has it stirred so much controversy over the years?

Read and discuss Jocelyn Chadwick's essay.

View excerpts from Ken Burns' Mark Twain video for PBS

Why Huck

Finn Belongs in the Classroom

Twain's work sparks the kind of frank

discussions about race and race relations that we need - and fear - to have

by Jocelyn

Chadwick, from the Harvard Education

Letter, Nov./Dec. 2000

In

the American Library Association's

recently published list

of the 100 most frequently challenged books of the 1990s, Adventures of

Huckleberry Finn ranked fifth. In fact, Samuel Clemens (a.k.a. Mark Twain)

had the dubious distinction of having written two of the only three

pre-twentieth-century books on the list. (The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

was #83, and Helen Bannerman's blatantly racist The Story of Little Black

Sambo was #90.) Clearly, much controversy remains about whether Mark Twain

had racist attitudes and whether he displayed those attitudes in his works,

especially Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Stereotypes

in his portrayal of the character Jim, excessive use of the racial slur

"nigger," and a paternalistic attitude toward African Americans are

among the charges made against Twain by his would-be banners. Are these charges

valid, and if so, do they implicate Mark Twain as a racist? Twain scholar Lou

Budd has asserted that Twain had "conflicting, conflicted attitudes"

about the racial issues of his time. And while I acknowledge the likely truth

in Budd's assertion, I would also argue that, given the time in which Twain

wrote, this can be seen as a minor indictment of Clemens the man and an even

lesser one of Twain the writer.

As

an African American, I know that I would rather be in a room with a person who

is working through his position on race and inequality than with an

incorrigible racist. Certainly racist attitudes of any kind, even if they stem

from "conflicting, conflicted attitudes" and membership in a culture

steeped in racial oppression, are unacceptable. But what are essential and

substantial are the decisions we make and the concomitant actions we take as a

result of our attitudes. We cannot, therefore, overlook the works of Twain that

do address the issues of race and stereotype. Clearly, Twain used his writing

to work through issues of race for himself and his society, and when I read

Twain's satires, I feel that he "gets it." Despite the culture

surrounding him, Twain understood deeply that racism is wrong. For Twain to

have depicted in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn a young hero who

questioned racial inequality and an African American who was caring,

compassionate, and strongly committed to his freedom was revolutionary indeed.

Moreover,

The Tragedy of Pudd'nhead Wilson more than nods at Twain's interest - or,

rather more appropriately, his concern - about race. In this novel Twain turns

on its proverbial ear the misconception of racial inferiority as evidenced

through language acquisition. Roxy, a slave woman who gives birth to a child

sired by the slave master, switches her baby with that of the slave master's

wife to avoid having her son sold down South. Both children grow up adapting

perfectly to their environments. Through the strength of Roxy's character and

the results of her actions, Twain makes clear that racial inferiority is not

inherent (as many in his time believed) and that voice and language can be

acquired by anyone who is put in the right environmental circumstances.

Consider

the Context

Twain's

views and depictions of African Americans must also be considered in the

context of African Americans' changing notions of themselves between 1835 and

1910. We know concretely through African American periodicals published during

the period and through slave narratives published both during the period and

during the early 1930s through the WPA project that African Americans viewed

themselves and their place in the North and South in varying ways. But one

constant that emerges over and over again - from the precise and articulate

periodicals such as The Elevator to

the narratives transcribed in heavy Southern dialect - is the desire to be

understood and appreciated as a thinking individual. This is a view of African

Americans that Twain, especially in Pudd'nhead Wilson, depicted

strongly. Paralleling this view, too, was an abiding and deep appreciation

among African Americans for any white person who displayed a scintilla of

concern, let alone a proclivity for voicing or displaying that concern. If the

African Americans of Twain's time could recognize the extraordinariness of

whites who dared question the prevailing social structures, can't we as

contemporary readers do the same?

By

now, I'm sure it's clear that I believe Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

must remain in classrooms throughout the country. It is educative not only for

African Americans, but for anyone sitting in an American literature survey

course. Does it stand in lieu of a good, substantive American history class

that addresses African Americans' experiences under slavery? Of course not, but

it certainly rounds out that experience. This is especially true in school

districts that for budgetary or other reasons do not have access to many novels

by African Americans who were Twain's contemporaries. But even if a district

does have a budget that allows it to purchase class sets of Frances Harper's Iola

Leroy, for example, it is still important to include a Twain novel,

especially Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, in the curriculum.

Through

the controversy surrounding this book alone, Twain brings into schools what all

of us in this country desperately need, yet fear, most: discussions - frank

discussions - about race, race relations, interracial relations, race language,

racial stereotypes and profiling, and, ultimately, true and unadulterated

racial equality. Does he ask all the pertinent questions and provide effective

and lasting solutions? No. How could he? How could African American writers

such as William Wells Brown, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Ralph Ellison,

George Schuyler, or even the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. do the same?

In

no way am I asserting that this novel is the ultimate answer to discussing race

relations in this country or even in the English/language arts classroom. What

I am asserting is that change begins, must begin, with one individual. And

while that one individual who connects with someone else will not cauterize the

racial chasm, the connection does create a ripple in the great racial ocean

that continues concentrically. By questioning racism in his own time and

provoking discussion in ours, Twain provides just such a connection for many

students.

Wednesday, March 4, 2015

Huck Finn Study Guide/ Review of Satire

AGENDA:

Select poet for Poet presentation/paper

Work in groups to finish Huck Finn study guide for PROJECT grade

Review SATIRE

Satire is used in many works of literature to show foolishness or vice in humans, organizations, or even governments - it uses sarcasm, ridicule, or irony. For example, satire is often used to effect political or social change, or to prevent it.

Satire can be used in a part of a work or it can be used throughout an entire work.

Satire examples from media include:

Franklin’s cartoon depicts a snake, cut into pieces, with each piece representing one of the colonies. The cartoon was published in every newspaper in America, and had a major impact on the American conscience.

The words “Join, or Die” eluded to the Indian threat, but much of the effectiveness of this image was due to a commonly held belief at the time, that a dead snake could come back to life if the severed pieces were placed back together. Franklin’s cartoon effectively grabbed the American peoples minds, and implanted an idea that endured even though the Albany Congress turned out to be a failure.

The image of the snake became the symbol for colonial unification, and was transferred to the colonial battle flag “Don’t Tread on Me”, and became part of the American spirit.

One of the cartoons printed by Nast, showed Tweed and the Tammany Hall Ring pointing at each other in answer to the question, “who stole the people’s money?” After this cartoon appeared, Tweed supposedly made the statement, “Stop them damned pictures. I don’t care what the papers write about me. My constituents can’t read. But damn it, they can see pictures.”

“If this is going to be a Christian nation that doesn't help the poor, either we have to pretend that Jesus was just as selfish as we are, or we've got to acknowledge that He commanded us to love the poor and serve the needy without condition and then admit that we just don't want to do it.”

A good example or a parody is the song “Girls Just Want to Have Lunch” by Weird Al Yankovic, which is a parody of the song “Girls Just Want to Have Fun” by Cyndi Lauper.

Following is an excerpt of Al’s song:

Here are some examples of sarcasm that are humorous, but still get their meaning across.

Select poet for Poet presentation/paper

Work in groups to finish Huck Finn study guide for PROJECT grade

Review SATIRE

Satire Examples

Satire can be used in a part of a work or it can be used throughout an entire work.

Many Faces of Satire

A satirist can direct the satire toward one individual, a whole country or even the world. It is sometimes serious, acting as a protest or to expose, or it can be comical when used to poke fun at something or someone.Satire examples from media include:

- “Weekend Update” from Saturday Night Live

- The Daily Show

- The movie Scary Movie

- The movies of Austin Powers

- Most political cartoons in newspapers and magazines

- The songs of Weird Al Yankovic

Political Satire

Satire commonly takes the form of mocking politicians. Consider the following examples of political satire.First Political Cartoon in America

It was one of the founding fathers, Benjamin Franklin, who is credited with creating, and printing the first political cartoon in America. Franklin was attempting to rally support for his plan for an inter-colonial association, in order to deal with the Iraquois Indians at the Albany Congress of 1754.Franklin’s cartoon depicts a snake, cut into pieces, with each piece representing one of the colonies. The cartoon was published in every newspaper in America, and had a major impact on the American conscience.

The words “Join, or Die” eluded to the Indian threat, but much of the effectiveness of this image was due to a commonly held belief at the time, that a dead snake could come back to life if the severed pieces were placed back together. Franklin’s cartoon effectively grabbed the American peoples minds, and implanted an idea that endured even though the Albany Congress turned out to be a failure.

The image of the snake became the symbol for colonial unification, and was transferred to the colonial battle flag “Don’t Tread on Me”, and became part of the American spirit.

Political Cartoon by Thomas Nast

Though Thomas Nast is credited with greatly influencing the American public during the Civil War, He is most remembered for his cartoon attack against political corruption in New York City. Nast created political cartoons in the 1870’s that exposed the corruption of Boss Tweed and New York’s corrupt Tammany Hall political machine.One of the cartoons printed by Nast, showed Tweed and the Tammany Hall Ring pointing at each other in answer to the question, “who stole the people’s money?” After this cartoon appeared, Tweed supposedly made the statement, “Stop them damned pictures. I don’t care what the papers write about me. My constituents can’t read. But damn it, they can see pictures.”

Political Satire of Stephen Colbert

“Tomorrow you're all going to wake up in a brave new world, a world where the Constitution gets trampled by an army of terrorist clones, created in a stem-cell research lab run by homosexual doctors who sterilize their instruments over burning American flags. Where tax-and-spend Democrats take all your hard-earned money and use it to buy electric cars for National Public Radio, and teach evolution to illegal immigrants. Oh, and everybody's high!”“If this is going to be a Christian nation that doesn't help the poor, either we have to pretend that Jesus was just as selfish as we are, or we've got to acknowledge that He commanded us to love the poor and serve the needy without condition and then admit that we just don't want to do it.”

Satire in Literature

Satire of Mark Twain

Satire can be found in literature as well. Consider the following explanation about satire in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn:The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was written shortly after the Civil War, in which slavery was one of the key issues. While Mark Twain's father had slaves throughout his childhood, Twain did not believe that slavery was right in anyway. Through the character of Jim, and the major moral dilemma that followed Huck throughout the novel, Twain mocks slavery and makes a strong statement about the way people treated slaves. Miss Watson is revered as a good Christian woman, who had strong values, but she is a slave owner in the story. She owns a slave called Jim, who runs away upon hearing that Miss Watson might sell him to New Orleans.

Other Forms of Satire

Satire examples can also be found in the following examples of irony, parody, and sarcasm.Irony

In irony, words are used to show the opposite of the actual meaning. The three kinds of irony are:- Verbal irony - where what you mean to say is different from the words you use

- Situational irony - compares what is expected to happen with what actually does happen

- Dramatic irony - uses a narrative to give the audience more information about the story than the character knows

“I'm aware of the irony of appearing on TV in order to decry it."A great example of irony in literature comes from The Gift of the Magi by O. Henry. It is a story of two people, much in love, who are very poor and want to give a Christmas gift to one another. She is very proud of her long, beautiful hair and he is equally proud of his pocket watch. The irony comes in to play when she cuts and sells her hair to buy him a chain for his watch, and he sells the watch to buy her combs for her hair.

Parody

A parody is also called a spoof, and is used to make fun or mock someone or something by imitating them in a funny or satirical way. Parody is found in literature, movies, and song.A good example or a parody is the song “Girls Just Want to Have Lunch” by Weird Al Yankovic, which is a parody of the song “Girls Just Want to Have Fun” by Cyndi Lauper.

Following is an excerpt of Al’s song:

Some girls like to buy new shoes

And others like drivin' trucks and wearing tattoos

There's only one thing that they all like a bunch

Oh, girls, they want to have lunch...

I know how to keep a woman satisfied

When I whip out my Diner's Card their eyes get so wide

They're always in the mood for something to munch

Oh, girls, they want to have lunch...

Sarcasm

Sarcasm is a sharp or cutting statement like a taunt or jibe, meant to really drive a point home. It can be meant to give pain and can include irony. On the other hand, sometimes you can make a point and still be funny.Here are some examples of sarcasm that are humorous, but still get their meaning across.

- Paul Newman said, “It's always darkest before it turns absolutely pitch black.”

- Steven Bishop remarked, “It's a catastrophic success” and “I feel so miserable without you, it's almost like having you here.”

- Oscar Wilde wrote, “I am not young enough to know everything.”

- “Marriage is the chief cause of divorce.”

- “I didn't like the play, but then I saw it under adverse conditions - the curtain was up.”

- “I never forget a face, but in your case I'll be glad to make an exception.”

Monday, March 2, 2015

Realism vs. Romanticism

Realism .vs. Romanticism

Characteristics of Romantic Literature:

Characteristics of Realist Literature:

o Themes: Highly imaginative and subjective; Emotional intensity; Escapism; Common man as hero; Nature as refuge, source of knowledge and/or spirituality

o Characters and setting set apart from society; characters were not of our own conscious kind

o Static characters--no development shown

o Characterization--work proves the characters are what the narrator has stated or shown

o Universe is mysterious; irrational; incomprehensible

o Gaps in causality

o Formal language

o Good receive justice; nature can also punish or reward

o Silences of the text--universals rather than learned truths

o Plot arranged around crisis moments; plot is important

o Plot demonstrates: romantic love, honor and integrity, idealism of self

o Supernatural foreshadowing (dreams, visions)

o Description provides a "feeling" of the scene

o Slave narrative: protest; struggle for authors self-realization/identity

o Domestic (sentimental): social visits; women secondary in their circumstances to men.

o Female gothic: devilish childhood; family doom; mysterious foundling; tyrannical father.

o Women's fiction: anti-sentimental heroine begins poor and helpless, heroine succeeds on her own character, husbands less important than father

Characteristics of Realist Literature:

o Emphasis on psychological, optimistic tone, details, pragmatic, practical, slow-moving plot

o Rounded, dynamic characters who serve purpose in plot

o Empirically verifiable

o World as it is created in novel impinges upon characters. Characters dictate plot; ending usually open.

o Plot=circumstance

o Time marches inevitably on; small things build up. Climax is not a crisis, but just one more unimportant fact.

o Causality built into text (why something happens foreshadowed). Foreshadowing in everyday events.

o Realists--show us rather than tell us

o Representative people doing representative things

o Events make story plausible

o Insistence on experience of the commonplace

o Emphasis on morality, usually intrinsic, relativistic between people and society

o Scenic representation important

o Humans are in control of their own destiny and are superior to their circumstances

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)